The Album

Classic Rock Review is built around the concept of the “album”, which we define as a collection of professionally recorded songs by a single artist published together usually through a single source of media. If that description sounds a bit convoluted, you may be right, but there really is no simple and concrete way to describe an atomic album. We don’t review singles or compilation sets, nor will we delve too deeply into different forms like live recordings, remastered works, or bonus tracks. Today we offer our first Special Feature (that is non-album review) on our understanding of this basic element of the site’s existence. We split this in two sections, looking at the evolution of the physical media followed by the practical casting of the music itself, which plays a big role on which specific eras we’ve decided to focus our reviews.

Classic Rock Review is built around the concept of the “album”, which we define as a collection of professionally recorded songs by a single artist published together usually through a single source of media. If that description sounds a bit convoluted, you may be right, but there really is no simple and concrete way to describe an atomic album. We don’t review singles or compilation sets, nor will we delve too deeply into different forms like live recordings, remastered works, or bonus tracks. Today we offer our first Special Feature (that is non-album review) on our understanding of this basic element of the site’s existence. We split this in two sections, looking at the evolution of the physical media followed by the practical casting of the music itself, which plays a big role on which specific eras we’ve decided to focus our reviews.

The Physical Media

Many people think “vinyl record” when they hear the term “album”, and this was certainly true for most of the eras that we review at CRR. But the truth is many types of media were used for recorded music before and after vinyl was prominent.

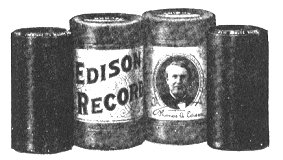

As we all learned in school, the first known recording was made by Thomas Edison in 1877 in his lab in New Jersey. The first commercial recordings became available in the next decade and these included various forms of discs and cylinders made of various materials including hard rubber.

As we all learned in school, the first known recording was made by Thomas Edison in 1877 in his lab in New Jersey. The first commercial recordings became available in the next decade and these included various forms of discs and cylinders made of various materials including hard rubber.

By the turn of the century, the first earlier materials were largely replaced by a rather brittle formula of shellac, a cotton compound, powdered slate, and a small amount of a wax lubricant. The shellac record was the prominent form of media for over half a century (reigning even longer than vinyl) until the 1950s. These recordings played at 78 rpm and only contained four to five minutes of music per side on each 12 inch disc. This presented a problem for certain genres where longer pieces were custom, especially classical and free form jazz. To work around this problem, record companies began releasing a set of records together as “albums”. In the 1930s this practice became commonplace for all genres, as record companies began issuing multi-disc collections of 78 rpm records by one performer or of one type of music. Artwork began appearing on the front cover and liner notes on the back, with most albums including three to four two-sided records, or six to eight songs each album.

The first vinyl records appeared around 1940 and were used for commercial recordings that were mailed to several radio stations because vinyl was less breakable. Vinyl was also used for recordings shipped to U.S. troops overseas during World War II, for much the same reason. Most of these were still played at 78 rpm and so they had the same time restrictions as their shellac counterparts.

The first vinyl records appeared around 1940 and were used for commercial recordings that were mailed to several radio stations because vinyl was less breakable. Vinyl was also used for recordings shipped to U.S. troops overseas during World War II, for much the same reason. Most of these were still played at 78 rpm and so they had the same time restrictions as their shellac counterparts.

On June 21, 1948, the Long Play (LP) 33⅓ rpm microgroove 12-inch record album was introduced by Columbia Records. In response, RCA Victor came up with its own format – a 7-inch, 45 rpm single with a large center hole. The 45s kept many of the same properties of conventional 78s, one song per side and multiple discs per album, but were much more compact in size. However, over time it proved much more efficient to release albums on a single LP rather than multiple 45s (or 78s, which continued to be mass produced alongside the newer formats until about 1960 in the U.S.). The 45 did prove useful for promotional “singles” as the hit parade and rock n roll eras began in the 1950s.

Also in the mid-1950s, the common “record player” began to feature multiple speeds, so that a single unit could play LPs, 45s, and 78s, rather than separate units for each. This feature did much to keep both the new formats viable and artists began making recordings for both LP and single 45 release (or both). Other enhancements in technology began to make recordings sound better than ever, including the introduction of stereo and equalization in the late 1950s and noise reduction later on. However, some problems did persist with vinyl records, especially LPs. The latter tracks on a side had lower fidelity because there was less vinyl per second available closer to the center of the disc. This problem sparked research in other types of media.

Eight-track cartridges, originally known as Stereo 8, were developed in the early sixties and experienced about a decade and a half of popularity through the 1970s. These cartridges used 3.75 inch magnetic tape that played in an endless loop tape with a track-change sensor that could be switched among four stereo “programs” played side on the tape. However, this format did not last long due to the inability to rewind, a feature available on 1/4″ cassette tapes, and the relatively low quality of sound as compared to higher end 2″ reel to reel tape. Soon the cassette tape took over the one area where the eight-track had reigned, the car stereo. For a while that format rivaled the LP for top format, especially after the development of mobile “boom boxes” in the late 1970s. The eight-track was phased out of production completely by 1982.

Eight-track cartridges, originally known as Stereo 8, were developed in the early sixties and experienced about a decade and a half of popularity through the 1970s. These cartridges used 3.75 inch magnetic tape that played in an endless loop tape with a track-change sensor that could be switched among four stereo “programs” played side on the tape. However, this format did not last long due to the inability to rewind, a feature available on 1/4″ cassette tapes, and the relatively low quality of sound as compared to higher end 2″ reel to reel tape. Soon the cassette tape took over the one area where the eight-track had reigned, the car stereo. For a while that format rivaled the LP for top format, especially after the development of mobile “boom boxes” in the late 1970s. The eight-track was phased out of production completely by 1982.

That same year Sony Corporation began producing symphonic music in a purely digital format called a Compact Disc (CD). Sampled at 44.1 kHz, the CD seemed to top all other formats in every phase. It had a greater frequency range from approximately 20 Hz to 20 kHz, as compared to LPs which had a bass turnover setting of 250–300 Hz and a treble rolloff at 10 kHz. Also, the digital format was the first to have “true stereo”, where other formats “bled” about 20% of one channel to the opposite channel and vice-versa. Finally, at 74 minutes a single CD held a nearly 50% higher capcity of music, as compared to the typical 40-48 minutes of a vinyl LP. The complete transition from vinyl to CD took over a decade as music consumers witnessed CD sections in record stores grow as the LP sections gradually shrunk and companies slowly made all mainstream material available on compact disc. But just when it seemed like the CD would be the dominant media for the foreseeable future, yet another innovation changed things.

Ever since the invention of the CD, several research groups and companies had been working on developing the next level standard. One such group was the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG), which sought to develop digital compression to make motion pictures available. The group progressively developed formats starting in 1993 with MPEG-1, 1995 with MPEG-2, and 1996 with MPEG-3. This latest format was idea for file-sharing of music and became commonly know as mp3 due to its online extension format (.mp3). Nearly overnight music was being shared on the Internet through various services like Napster and CD sales began to plummet. After some desperate lawsuits and other tactics, the major labels eventually submitted to the new trend and today most albums are available in digital format and most songs can be purchased separately.

The Logical Album

As we mentioned earlier, music albums first physically consisted of multiple 78 rpm discs before later being released on vinyl LPs. However, there was also an evolution of the “logical” album.

At the dawn of the rock era, albums were simply a collection of songs, mainly a sales item and barely a cohesive, artistic statement. Songs were often developed with strict formulas and included as “fillers”, with a handful of popular songs being the main sales draw. The most popular songs were often featured on many albums, making a definite lineage of sequential works hard to trace for many early artists. Most songs were written by company employed songwriters or teams and creative control was placed firmly with record company producers.

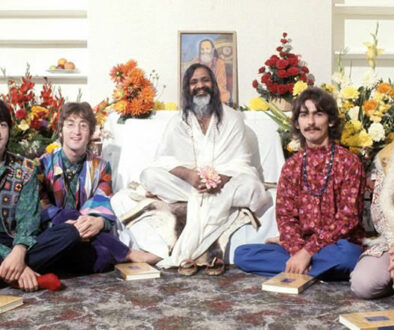

This all started to change in the 1960s. Led by artists like Bob Dylan and the Beatles, original compositions by top artists went from a tiny minority at the beginning of the decade to a vast majority by the end of the 1960s. Released in 1963, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan contained 12 originals out of 13 tracks and may well be one of the first “albums” as we at Classic Rock Review have come to define that term. The Beatles were also releasing albums as early as 1963, but they had different sets of albums for the UK and the US through 1966. In fact, the Beatles music was delayed from being released on CD until 1988 because there was a long debate on which path to follow for the first seven or eight releases, until the UK releases were deemed “official”.

This all started to change in the 1960s. Led by artists like Bob Dylan and the Beatles, original compositions by top artists went from a tiny minority at the beginning of the decade to a vast majority by the end of the 1960s. Released in 1963, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan contained 12 originals out of 13 tracks and may well be one of the first “albums” as we at Classic Rock Review have come to define that term. The Beatles were also releasing albums as early as 1963, but they had different sets of albums for the UK and the US through 1966. In fact, the Beatles music was delayed from being released on CD until 1988 because there was a long debate on which path to follow for the first seven or eight releases, until the UK releases were deemed “official”.

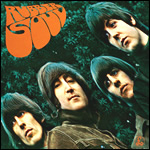

Also, during the height of the Beatles phenom, hit songs were intentionally kept off albums so that the most dedicated fans would buy both the LP and 45. For this reason, two new albums were created in 1988 (Past Masters I & II) to include the vast amount of A and B sides which were never included on any official Beatles album. Even though the album Rubber Soul had significant differences between the two versions, it may be the first work that was recorded as a cohesive “album” and not just a collection of songs. American musician Brian Wilson was so inspired by this album that he set out to produce his own masterpiece for The Beach Boys called Pet Sounds in 1966, which itself inspired the Beatles next album Revolver.

Also, during the height of the Beatles phenom, hit songs were intentionally kept off albums so that the most dedicated fans would buy both the LP and 45. For this reason, two new albums were created in 1988 (Past Masters I & II) to include the vast amount of A and B sides which were never included on any official Beatles album. Even though the album Rubber Soul had significant differences between the two versions, it may be the first work that was recorded as a cohesive “album” and not just a collection of songs. American musician Brian Wilson was so inspired by this album that he set out to produce his own masterpiece for The Beach Boys called Pet Sounds in 1966, which itself inspired the Beatles next album Revolver.

Classic Rock Review chose the year 1965 to begin our regular reviews, because it is when we believe the classic rock album first proliferated on all fronts – with most songs composed by the artist, the album a cohesive unit, and enough quality works available to review. There were certainly several classic works available before this time but those were fewer and further between. Similarly, we chose 1999 as our endpoint because that was just before the mp3 revolution, when the whole concept of “the album” began to break down and single, individual songs were treated (once again) as autonomous units. While this is beneficial to the music listener in many ways, what is lost is the artwork, the sides, the sequence, and a lot of the conversation that many of us knew and loved in earlier days.

~