Bringing It All Back Home

by Bob Dylan

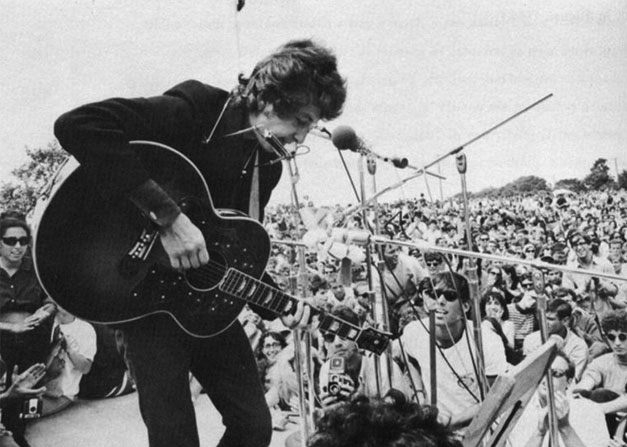

Perhaps the most lyrically potent album ever, Bob Dylan delivered a masterpiece with his fifth overall album, Bringing It All Back Home, released 50 years ago today on March 22, 1965. On this record, Dylan’s lyrics became more stylistic and surreal, with the composer employing stream-of-consciousness rants influenced by dreams and the result of isolated and intense writing binges. Most impressively, the words are striking and profound and persist in their relevance a half century later, as it personifies the absolute reach for the ultimate heights even if it risks an ultimate fall. Musically, this album featured Dylan’s first “electric” recordings as he worked with a full backing arrangement on the tracks on the first side. While the album’s second side features traditional acoustic folk songs, there is a steady vibe that unifies the album from end to end and makes it an indisputable work of art as a whole.

Perhaps the most lyrically potent album ever, Bob Dylan delivered a masterpiece with his fifth overall album, Bringing It All Back Home, released 50 years ago today on March 22, 1965. On this record, Dylan’s lyrics became more stylistic and surreal, with the composer employing stream-of-consciousness rants influenced by dreams and the result of isolated and intense writing binges. Most impressively, the words are striking and profound and persist in their relevance a half century later, as it personifies the absolute reach for the ultimate heights even if it risks an ultimate fall. Musically, this album featured Dylan’s first “electric” recordings as he worked with a full backing arrangement on the tracks on the first side. While the album’s second side features traditional acoustic folk songs, there is a steady vibe that unifies the album from end to end and makes it an indisputable work of art as a whole.

While they remained firmly within the realm of folk music, the very titles of Dylan’s 1964 albums (The Times They Are a’ Changin’ and Another Side of Bob Dylan) signaled that the composer may traverse the strict standards of folk music, even if they simultaneously established Dylan as the leading folk performer of his generation. He retreated to Woodstock, NY during much of the summer of 1964, along with fellow folk singer and then-girlfriend Joan Baez. According to Baez, Dylan would stand at a typewriter in the corner of a room, “tapping away relentlessly for hours.” In late August 1964, Dylan had a private meeting with The Beatles in New York City which apparently had a radical effect on both the artistic entities.

Later in the year, Dylan and producer Tom Wilson began experimenting with techniques of fusing rock and folk music. After a few failed attempts at overdubbing electric backing tracks to existing acoustic recordings, the composer and producer brought in a full band for sessions in January 1965. Here, for the first time, Dylan employed his unique method of rapidly “teaching” each individual session man (who had no prior awareness of the material being recorded) exactly he wanted their individual part to be. Amazingly, the entire album was recorded in just a few days, with the entire second side recorded on January 15, 1965.

Those songs recorded for the second side were intentionally stripped down, usually with just Dylan and his acoustic guitar/harmonica accompanied by one other single player to add the slightest bit of flavoring and counter-melody to the otherwise raw tracks. While the production team could have easily released full “electric” versions of every track on this final album, it is rather ingenious the way the second side was presented as almost a natural bridge between Dylan’s previous work and the new direction he was heading, even on the first side of this very album.

Bringing It All Back Home by Bob Dylan |

|

|---|---|

| Released: March 22, 1965 (Columbia) Produced by: Tom Wilson Recorded: Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, January, 1965 |

|

| Side One | Side Two |

| Subterranean Homesick Blues She Belongs to Me Maggie’s Farm Love Minus Zero/No Limit Outlaw Blues On the Road Again Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream |

Mr. Tambourine Man Gates of Eden It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue |

| Primary Musicians | |

| Bob Dylan – Lead Vocals, Guitars, Keyboards, Harmonica Al Gorgoni – Guitar Kenny Rankin – Guitar Paul Griffin – Piano, Keyboards William E. Lee – Bass Bobby Gregg – Drums |

|

Looking at the second side first, it begins with the oldest song on the album, “Mr. Tambourine Man”, written over a year before the album’s release and performed many times through 1964. This well-crafted folk song with highly poetic lyrics, features Dylan’s acoustic nicely complimented by the slightest electric guide guitar of Bruce Langhorne. Less than a month after its release on Bringing It All Back Home, The Byrds released their own interpretation of the song, which reached number one on the Billboard charts and helped spawn their debut album of the same name. Lyrically, the song was influenced by French poet, Arthur Rimbaud, and Italian filmmaker, Federico Fellini with focus on a central muse who has been interpreted as anyone from an American Indian shaman to Jesus Christ. Of course, the similarities to an LSD trip cannot be disregarded;

Take me disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind, down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves of the haunted frightened trees, out to the windy beach far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow / Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free, silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands with all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves, let me forget about today until tomorrow…”

“Gates of Eden” is nine verses of pure folk intensity, where Dylan commands full attention as he tells fables and fortunes about universal and existential stories, with Dylan performing the entire song solo end to end. This song was also written in late June or July 1964, and has clear religious overtones with the Biblical location of pure peace and serenity within a turbulant universe. With little variation throughout its five minute duration, Dylan masterfully commands total attention during each autonomous viginette, with a single harmonica note separating each verse and alerting to a new start. Further, the lyrics describe historical and mythical figures alike;

With a time-rusted compass blade, Aladdin and his lamp sits with utopian hermit monks, side saddle on the golden calf and on their promises of paradise you will not hear a laugh all except inside the gates of Eden…”

The most haunting and pure dark folk track on the album, “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” best displays the pure genius of Dylan with a song that is a perfect message both musically and, most especially lyrically. First performed live in October, 1964, this grim masterpiece features Dylan’s best acoustic performance (with no harmonica!) as well as some of his most memorable lyrical images, which express the composer’s rants against hypocrisy, commercialism, institutionalism, and contemporary politics and, decades later, Dylan has named this track as one that means the most to him. After the brilliant cascade of lyrical genius, the track concludes with the most profound line of all;

And if my thought-dreams could been seen, they’d probably put my head in a guillotine, but it’s alright, Ma, it’s life, and life only…”

The album concludes with “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” which, despite its name, is a much brighter acoustic song than anything else on side two and has an almost electric vibe. William E. Lee offers refrained but interesting bass guitar to the acoustic strumming and dynamic melodies of Dylan’s vocals. The song’s subject may have been the folk protest movement in general or Baez in particular, or even both. In any case, this offers a perfect conclusion to Bringing It All Back Home and leaves an almost deafening reverberation in the listener’s ear after the song concludes.

Rolling back to the beginning, this brilliant album has a rather unpolished start as the intro to “Subterranean Homesick Blues” is slightly cut off. However, once this song fully launches, it never relents for one single moment, with its only real flaw being that it ends too soon. Here Dylan blends the musical influences of Chuck Berry and Woody Guthrie along with a lyrical style similar to the writings of Jack Kerouac. Released as a single ahead of the album, “Subterranean Homesick Blues” became Dylan’s first Top 40 hit in the US, as well as a the Top 10 hit in the UK. Dylan employs a completely different vocal style on “She Belongs to Me”, a much smoother song musically than the opening track. While his vocalizing has long been the subject of debate and some derision, it is really quite amazing how Dylan can shift gears from track to track. Musically, a gently strummed acoustic is complemented by the picked electric guitar of Langhorne along with a subtle rhythm track and Dylan also executes a few of his finest harmonica leads on this song.

“Maggie’s Farm” may very well be the ultimate counter-counterculture song, exposing some of the hypocrisies of a rebellion against “the establishment” while implementing even stricter standards within itself. Armed with some of his more brutal lyrics, Dylan unambiguously screeds through this explicit poetry and clarion declaration of independence. Essentially, this is an announcement of his musical transformation, which found further importance when Dylan performed it as the opening tune during his defiant electric set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival in August of that year.

I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more / Well, I try my best to be just like I am but everybody wants you to be just like them, they sing while you slave and I just get bored, I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more…”

As cynical as the previous tracks are, “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” completely pivots in the opposite direction, almost like an extremist love song. The very title (a mathematical equation which results in “absolutely unlimited love”) indicates the complete offering of one’s existence to a significant other, in this case Dylan’s future wife Sara Lowndes. Another complete departure for Dylan is “Outlaw Blues”, a rollicking, bluesy and about as heavy as rock and roll came in 1965. In fact, this song could, at once, be a true ancestor to bluesy jam bands as well as the hard rock and heavy metal which arrived a half a decade later. With “On the Road Again”, Dylan takes a large step forward both musically and lyrically. This strong rock/blues track with especially potent drums by Bobby Gregg, contain lyrics written in the spirit of Kerouac’s novel On the Road but with a definite original edge;

Well, there’s fist fights in the kitchen, enough to make me cry / The mailman comes in and even he’s gotta take a side / Even the butler, he’s got something to prove / Then you ask why I don’t live here, Honey, how come you don’t move?”

The album’s first side ends with a bit of levity in the false start of “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream”. Once the song really kicks in, it employs a true stream-of-consciousness and may have the most surreal lyrics on the album. The song’s title alludes to the track “Bob Dylan’s Dream” from his 1963 album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, but as an almost satirical sequel to that serious folk song.

Upon its release, Bringing It All Back Home reached the Top Ten on both sides of the Atlantic and has continued to grow in stature and importance in the half century since its release. Later in 1965, Dylan would record and release another masterpiece, Highway 61 Revisited, an album Classic Rock Review will examine on August 30th, the 50th anniversary of that album’s release.

~

Part of Classic Rock Review’s celebration of the 50th anniversary of 1965 albums.

Bob Dylan Wins Nobel Prize | Roots Rock Review

October 13, 2016 @ 7:26 pm

[…] music came in the mid 1960s with classic albums such as The Times They Are a’ Changin’, Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde. This latter album was cited by the Nobel […]

Top 9 Album Closing Songs | River of Rock

August 1, 2018 @ 7:10 pm

[…] Dylan’s classic 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home concludes with the aptly titled “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”. Despite its […]

The Times They Are a Changin' | Roots Rock Review

January 16, 2019 @ 9:30 am

[…] by “going electric” and releasing a quartet of masterpieces through the mid 1960s, Bringing It All Back Home (1965), Highway 61 Revisited (1965), Blonde On Blonde (1967) and John Wesley Harding (1968). With […]